BY LISA KRAUS

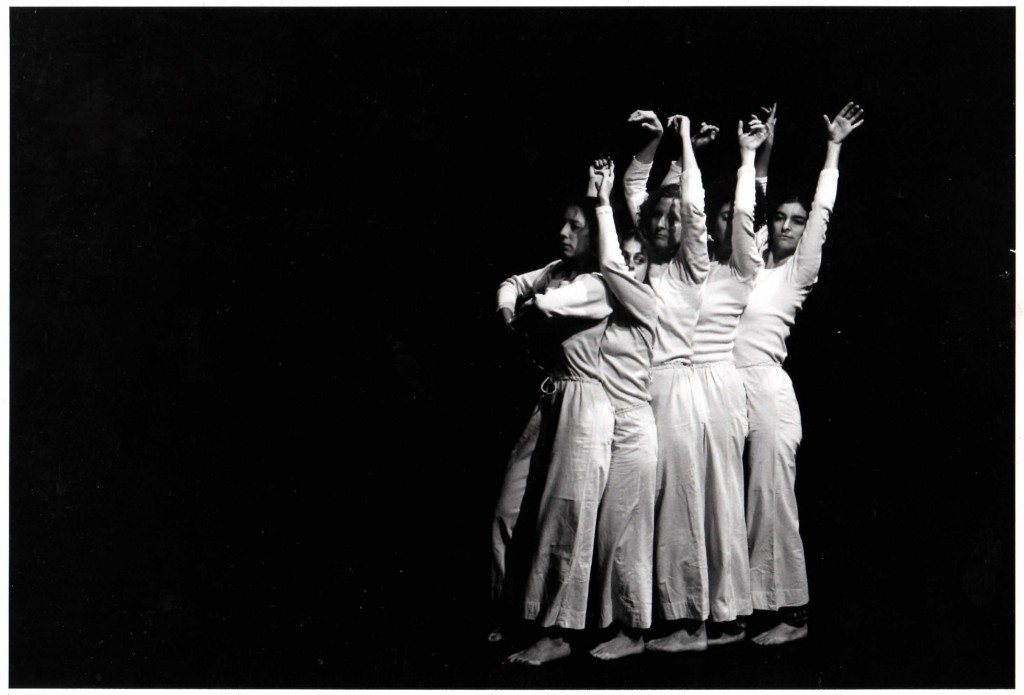

Lisa Kraus (seen at the far left in this photo) is the curator of Trisha Brown: In the New Body. She danced for the Trisha Brown Company from 1977 to 1982, and later set Brown’s dances on other companies, which she continues to do today. She has written widely about dance, curates the Bryn Mawr College Performing Arts Series, and founded thINKingDANCE (thinkingdance.net), which is dedicated to critical coverage of dance.

Discovery

I had no idea what to make of it, this wild improvised 1975 show by the legendary troupe Grand Union where Trisha Brown was folding, twisting, and stretching through her joints, tracing invisible architectures around herself. My initial response was incomprehension. It was not like any dancing I’d seen before. But the performance stayed with me—and two years later, I was a member of the Trisha Brown Dance Company.

Early on, I danced Floor of the Forest, one of Brown’s equipment pieces. Clothing is threaded onto a grid of rope suspended parallel to the floor—the dancers crawl in and out of it, slipping arms and legs into sleeves and pants legs and then hang suspended in air. Was this dance? Was Brown’s earlier experimentation with harnesses and ropes, like Man Walking Down the side of a building or Walking on the Wall at the Whitney Museum, dance? The distinction Brown made for herself was between kinds of action: pedestrian movement (which the Walking pieces were, although tipped sideways in relation to gravity), gesture (which she used in Roof Piece, and some of her work at Judson Church like Homemade) and dance movement which was non-symbolic, non-functional, and could involve more technically challenging balances and coordinations.

A Pivotal Moment

When I joined the company Brown had just developed ways of mapping—and teaching—her rapidly developing personal movement language, and soon began choreographing for the proscenium stage. The first dance I learned, Line Up, pioneered a working method that would be a cornerstone of Brown’s dances for years. Improvising with the instruction “line up,” the dancers responded to each other’s choices in real time. The second dance was Locus, a series of four solos, each from the same score and danced within a cube placed within a grid of multiple cubes. The dance is precise—with each movement referring to a specific point on the cube—and open, with sections when the dancer chooses her spatial placement or splices sections of the solos together.

Rehearsals were full of revelations. Brown would cheerlead us, creating forms that led us to dance as we never had before. At times rehearsal was hard to hang in for, as when myriad tiny adjustments were needed to hit interactions precisely in what might have looked to an outsider like a nebulous cloud of group movement. This was not simple unison dancing. It involved a series of interdependent reactions, which was not a common thing at that time.

Art Stars

In the late 70s and throughout the 80s, Brown began a series of collaborations with big name arts colleagues—Robert Rauschenberg, Fujiko Nakaya, Donald Judd—which led her to major venues on the world stage. Set and Reset (1983)— Rauschenberg supplied the design and Laurie Anderson the music—premiered right after I left the company. The surging, daring ebbs and flows and throw-and-catch partnering were the most exciting group dancing I had ever seen. It owed a lot to Steve Paxton; his development of contact improvisation is what had schooled the dancers with weight sharing and lifts arising from momentum rather than muscularity.

Brown’s movement interests evolved: What is men’s movement? How does counterpoint work? How might her movement sensibility incorporate emotional content? Seeing Brown in her final solo, If you couldn’t see me (1994), I was struck how can one person’s back be so communicative. How can she, dancing alone and never turning to face us, evoke such an elegiac quality of beauty and loss simultaneously?

Ever New Horizons

Nearly two decades after leaving the company, I was invited to restage works by Brown in Europe and the U.S. Around this time, Brown created PRESENT TENSE (2003), almost a summation of preoccupations from earlier dances. She carried forward ideas like “going in two directions at once,” simplifying the stage picture, often by doubling the action, and upping the ante on partnering’s complexity. It’s vibrantly staged with the playful contribution of the painter Elizabeth Murray.

When Brown made O zlozony / O composite (2004) on the Paris Opera Ballet, it was a whole new challenge—she had never set a dance on a ballet company and here were some of the world’s very best ballet dancers. Brown became intimate with classical dance in order to shift back and forth between its conventions and her characteristically un-balletic use of flow and weight. Buoyed along by Laurie Anderson’s hushed score, Brown drew out the expressive refinement of the dancers and melded ballet’s approaches to lifts and flight with her own.

Brown’s works have all combined her appetites for new physical discovery, conceptual playfulness, and structural rigor. No one has ever harnessed my attention more fully and completely with the diabolical complexity and daring of her physical presence. Let me share with you what has brought me infinite joy and artistic sustenance over the course of forty years. I hope it will transport and enrich you, as it has me.

—Lisa Kraus

Photos: Top by Babette Mangolte (top); John Waite (middle); Nan Melville (top).