“Almost nothing in my modern dance training prepared me technically for the movement vocabulary Trisha was developing.”

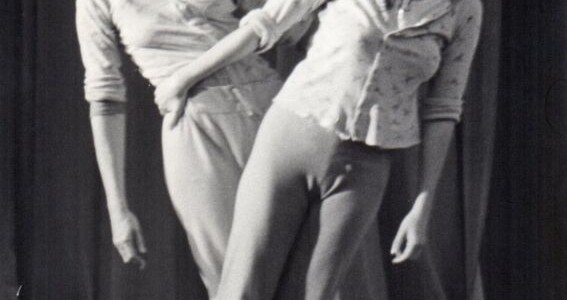

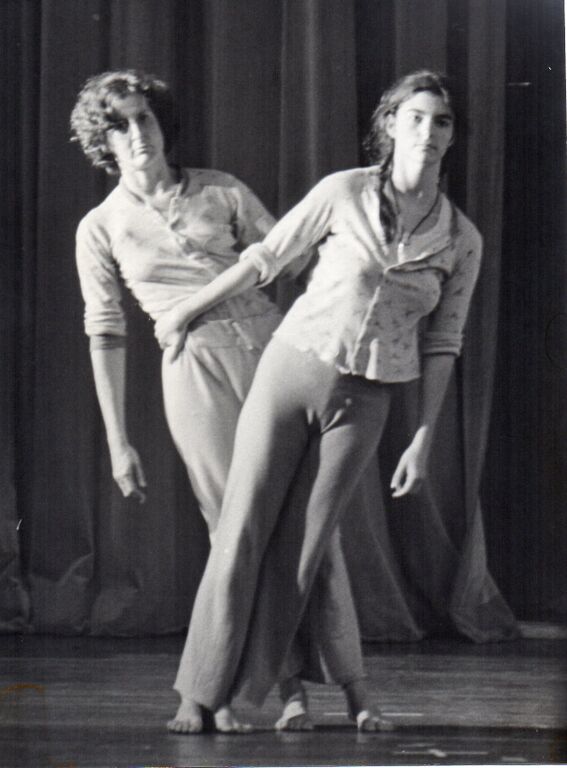

Elizabeth Garren danced for (and with) Trisha Brown from May 1975 through December 1979.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work? And was that when you first connected with her work?

Elizabeth Garren: When I visited New York City for two months in 1973 to study dance and attend performances, I was surprised it was Trisha’s relatively non-dance work that most captivated me—think Trisha and Sylvia Whitman doing Pamplona Stones in her loft. I was taken with her stark creativity, elegant tempo, and droll humor. I was somewhat prepared for her style from Grand Union performances in Minneapolis, but surprised how her work stood out to me compared to everything else I saw in New York, like a sharp knife cutting through fat.

When she brought her company to the Walker Art Center in 1974, I volunteered to be the extra dancer they needed for their performance there. After that night’s show, I showed the company a jolly good time, walking them to dance at a biker bar through an abandoned railroad lot near my home—we got halfway there before they demanded to return home asap, where we danced to Stevie Wonder and Aretha. That next spring, Trisha phoned me in Minneapolis to ask if I’d be willing to move to New York City asap as she was gathering together a new company. Wow. I arrived fresh off the train with my duffle bag, took the elevator up to the 5th floor of 541 Broadway and launched into learning a piece called Locus, which we would perform in a loft showing three weeks later. (Idol Yvonne Rainer watching!) Almost nothing in my modern dance training prepared me technically for the movement vocabulary Trisha was developing. At least I was well versed in improvisation, in movement as well as life.

Q: What were rehearsals like?

EG: Exit the elevator, Ginger’s long toenails clicking over for a proper wiggly greeting, dumping my stuff, lying on the floor to contact the part of me I would need for the hours of dancing ahead: availability of every joint of my body, a dropping away of all my dance technique from the past, a sense of multidimensional awareness visually/spatially to master unison movement with no outward musical tempo, trying to match my “heft” with Trisha’s. At the time, all of us did Elaine Summer’s ball work, informally, individually, checking in verbally as we rolled around. Very little, if any, transition to standing and dancing.

With Locus, she handed already created movement to us, then asked us to make improvisational choices about where to take the movements spatially on the marked floor grid, with whom to join up in unison, when to break apart from unison etc., which made the piece come alive for us and required total presence of mind. Later, Solo Olos was to require even more such mental aliveness, especially for the “caller,” Mona Sulzman. And in Line Up, how about precisely capturing five- to ten-second chunks of freely improvised moments of lining up, getting five people to agree on exactly what, when, and where it had just elusively happened, then rigorously setting it in stone for the ages? Each time we prepared to perform Line Up, Trisha became the nitpicker from hell, knowing the piece could dissolve into sloppy, rather then precise, casualness. We hated those rehearsals, maybe Trisha did too. Drudge work, but she knew how to make the jewelry shine.

Q: How did Trisha talk about the work to you?

EG: If Trisha talked about the work at rehearsal, it was focused on the practical task at hand, not conceptual or the bigger view. Looking back, she had to patiently work to divest me of my tendency to add too much expression to my movement. I had been trained to project to the last row in a theater, often being asked to smile or look like I was having fun. Oh boy. Settle down, Elizabeth.

Q: What was, for you, most challenging to master?

EG: What was challenging to master was dancing anywhere near as good as Trisha, and as I said, in unison with her. I remember the first time I was able to match the timing of Trisha’s “squat to scoop, rise, and fall into anther squat” move in Locus. It was not from watching her and controlling my tempo with muscles as I had before, but from finally feeling myself as Trisha seemed to feel herself . . . the deepness of her hip fold, her untrapped pelvis, the comfort with falling taking its own time, no rush, no fuss, just the uncluttered presentness of this, then that, continuing, then continuing some more.

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be?

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be?

EG: This may surprise you, but it would be Locus as danced to Al Green’s “Simply Beautiful.” And I would be doing it with Trisha, Judith, and Mona, as we did in one of our first (1975) residencies, on the grounds of Art Park, in a hot breezeless tent, with the odd groups of tourists wandering through our rehearsals, many asking, “Is this yoga?” The heat must have gotten to Trisha because she uncharacteristically asked us to play some Al Green songs as we ran through it again. As rigorous and relatively undynamic as Locus is, it is rich and body friendly to dance. But when the lazy back beat of the Reverend came on, it took Locus to the moon—which is kind of like an island. Up till then we had danced only in silence. Now for a few minutes we let go of all rigor and danced the boundless heck out of Locus. Mmmm, mmm.

Come to think of it, this experience was a preview of what I learned later on with Trisha, when I was a better dancer. By the time I did Glacial Decoy, and her choreography had opened up spatially and dynamically, to dance her work well required both rigor and boundlessness. And although I left the company after Glacial Decoy, I saw these qualities meshed to perfection in the original performances of Set and Reset.

Q: How did Trisha’s dances evolve during your time with the company?

EG: Once she tapped a vein of a nontraditional movement source, which I felt she developed during my time in the company, through strict structure—example: with Locus, the cubes and alphabetical match up of points to letters in a sentence—she could open up on everything else. For me, Glacial Decoy finally released us in space and movement dynamics. All of Trisha’s cleverness was set loose. Thrilling to witness.

Q: What stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today? What have you carried with you?

EG: Looking back, I was dancing to experience life as an adventure, not to be an artist. I don’t do my own work in that sense. What stays with me is how lucky I was to be there in the beginning, when I could know Trisha as a person . . . ok, a luminously quiet genius. I saw firsthand how genius work is done: methodically, daily, thoughtfully, intensely, ongoingly. Pretty much unglamorously. Addictively, maybe? I also saw the increasing behind-the-scenes work of raising money, promoting, meetings, keeping “the machine” of success going, which meant less and less time in the studio alone with her muse. And, especially in the early years before she knew how it really worked, learning to say goodbye to beloved company members who chose to leave the company just when they were getting really good at doing her work.

What do I carry with me from Trisha’s work? Trisha herself, as someone I know and love, and the knowing how much beauty she created like a pebble in the pool to ripple out into everyone and everything around her.

Photos: Elizabeth Garren with Trisha Brown rehearsing Pamplona Stones (photographer unknown); Elizabeth Garren photo by Elizabeth Garren.