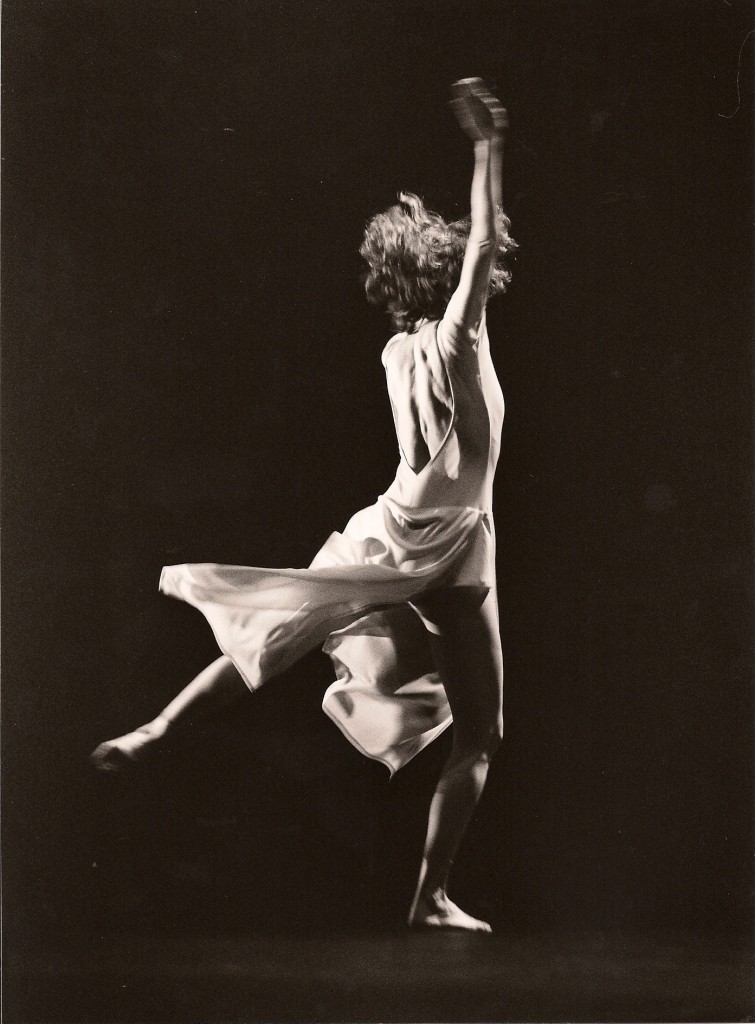

The letter below was sent to Trisha Brown after she performed her solo If you couldn’t see me at the American Dance Festival in Durham, NC in June 1994.

References which would’ve been clear to her but not to you, probably, include: Betsy Frederick, a mutual friend in Albuquerque, New Mexico; the costume, which consisted of a very scoop-backed leotard, tights, and a long panel from the waist, front and back; “Bob’s device” which is the idea of not facing front; Bob himself, the artist Robert Rauschenberg, who made the music and costume; the lighting designer is Spenser S. Brown.

The Trillium of the last sentence is another Trisha Brown solo which she performed at the Judson Memorial Church in 1962. [S.P.]

27 June 94

Durham, NC

Dear Trisha,

I wrote to Betsy Frederick yesterday including something about your solo. And it lingered. I woke with your scapulae floating in the part of the brain which remembers such things.

Spenser, Bob and especially you have made a deeply satisfying artifact. The costume is exactly right. It is impossible to separate it from the light, because you are clothed in both. The revel and revelation of your spinus erectae, scapulae and delicate pearls of the spinous processes in the lumbar, side-lit for maximum bas-relief, sent a gasp through the audience.

You cannot know, but may have heard from others, what the sculpture of your back can accomplish. It is Indonesian in line and volumes: richly shadowed and starkly lit in its highlands, it became an abstraction shifting from an anatomical event with muscles like a whippet to a large looming face to a mask—something alien and frightening although weirdly comic as the rest of the body reconnects and we see again a back.

Bob’s device gives us three things in the end. It refutes the frontal convention, as you did once before, with the standing figure in For MG: the movie, so Magritte-like. It gives the solo a real task to accomplish—a simple idea, one we can examine for effects and learn from: for instance, the enlivening of the upstage space and how the black curtain is not just an expanse of dark background to contrast with your lit figure and push you toward us, visually. Your orientation declares it a dark vista, and it acquires a dimensionless depth.

And last, facing up relieves you of facing us. I believe you are essentially a private person who almost perversely, mothlike, headed for the limelight. Your dances are never less than brilliantly constructed and (bless your excellent company) danced. Yet they do not yield to our gaze. They are hyperactive; over-rich in thrust, drop, dart, scamper, buck, throw, lift, swoop, twist. They don’t settle happily onstage. They twist metaphorically too, subtlety and irony being common.

The performance style is sometimes like seeing animals in one’s headlights. Or an insect, however beautifully exotic, pinned. Who was that masked woman?

Facing upstage, you aren’t blinking uncomfortably in the light of our avid eye. You know you cannot know or concern yourself with how you may look to us, and so try to deflect us. With that issue aside and privacy assured, you seem to relax and really put out. Lordy, how you dance. Pure, assured, full-bodied, wild and fully self-knowing.

We are not watchers but onlookers. You are not our focus exactly but a medium mediating between something, some unknowable or unthinkable vision in the upstage volume or, sometimes beyond into the velour fathom into which we project. This illusory upstage spatial pliability—from positive dancing figure on black to negative dancing figure in front of potentized unguessable empty space is deeply satisfying, mythic and wholly theatrical.

I grew fond of the music. It sets you up well, for one thing. We watch the front curtain lights, beginning to…drift, in spite of ourselves. Then the curtain rises and the black is a color, not an absence. Our eyes see you and then the moonscape of your back, the chiaroscuro which, as you raise your arms, fascinates us bringing us closer and rendering you enormous, a woman with a whole scene on her back. It is like puppets and how we adjust to their scale, along with the unsettling fact that the puppeteer’s whole body is visible and active, too.

This is analogous to the figure-ground flipping revealed as the dance progresses—partial or full-figure, back is front, front is back, looks as on-lookers. When, in philosophy, so much is achieved and the means are minimal, the word used to describe the effect is “elegant.” And so it is.

One quibble. The ending. We have gotten used to these materials, and having made your move, it is time to stop. The light again is dressing you. Your arms float high then drop and swoop to their asymmetrical positions beside you, fingertips alert to your surface and your figure’s suddenly quiet mass. The light fades; just right. But the music—was it, too, faded out? It felt like acoustical short shrift. One further flip could be achieved if it played on a moment in darkness—we could lose all our visual foci and be engulfed in the black you have sourced; so we might experience what we have seen beyond you on the stage, but only as a distance. We could be you in it, or experience what you might have felt as you played with it, faced it. The music would keep us entranced as our bearings fade, your visual surface recedes. We could shift from the specificity of the visual solids to more oceanic senses—the drone and the dark.

I run on. Let me just say that I think Trillium would be proud of you.

Looking forward:

Love, Steve

______________________________________

Letter To Trisha reprinted with kind permission, published originally in Contact Quarterly, Vol. 10 No. 1, Winter/Spring 1995.

Steve Paxton was born in Arizona in 1939. He was a member of the José Limón Company in 1959 and a member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company from 1961 to 1964. He was a founding member of the seminal dance collectives Judson Dance Theater (1962–64) and Grand Union (1970–76). Throughout his career, Paxton’s singular investigation of improvisation has opened new ideas in creating and composing choreographic work. It was during his time with Grand Union that he first formulated Contact Improvisation, a dynamic, partner-based dance that is now practiced worldwide. From Contact Improvisation, he developed the movement practice Material for the Spine in 1986, which examines movement outward from the core of the body.

Photo: Klaus Rabien