“With Trisha, movement, any movement, was a seduction from the unknown, an invitation to see what could/would happen if. “

Elizabeth (liz) Carpenter was a dancer with the Trisha Brown Dance Company from 1989 to 1995.

Elizabeth (liz) Carpenter was a dancer with the Trisha Brown Dance Company from 1989 to 1995.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work?

Elizabeth Carpenter: I was dancing with the Joe Goode Performance Group in San Francisco, and a dancer friend of mine said Trisha Brown Company was in town and auditioning. My friend wanted to audition and asked me to go with her. So I did. I fell in love with the strange interdependency/contingency physicality of it—unlike anything I’d ever done before. It was a new physical conundrum to master and it felt exhilarating. They hired me and brought me to New York. Leaving Joe, having been an original member of his company, was a hard decision, but I couldn’t resist what I’d experienced at that three-day audition. Of course I’d heard of Trisha Brown, but had never seen the work before. I saw the company perform for the first time that weekend. I remember thinking, “It sure doesn’t look as complex as it feels.” I was hooked, and remained hooked, as the repertory took me through numerous stages and refinements of the interdependency/contingency dynamic.

Q: What were rehearsals like?

EC: I guess I would say that like the finished product, rehearsals were meticulous, and relentless in perfectionism that somehow yielded playful exploration. The most challenging thing to master was related to older pre-your-era works where the reproduction of an originator’s idiosyncrasies was required. Videos of rehearsals when works were being created were used to pass repertory through generations. Separating peculiarities of an individual from the choreography was no easy feat. The natural connection was the material itself. It was like swimming. You and the water are one, and you’re both predictable and unpredictable simultaneously. And yet, you know—without knowing—how to do it.

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be and why?

EC: Lateral Pass, because it’s so whacky and joyful and exhausting and every dancer gets to shine gloriously.

Q: How did Trisha’s dances evolve during your time with the company?

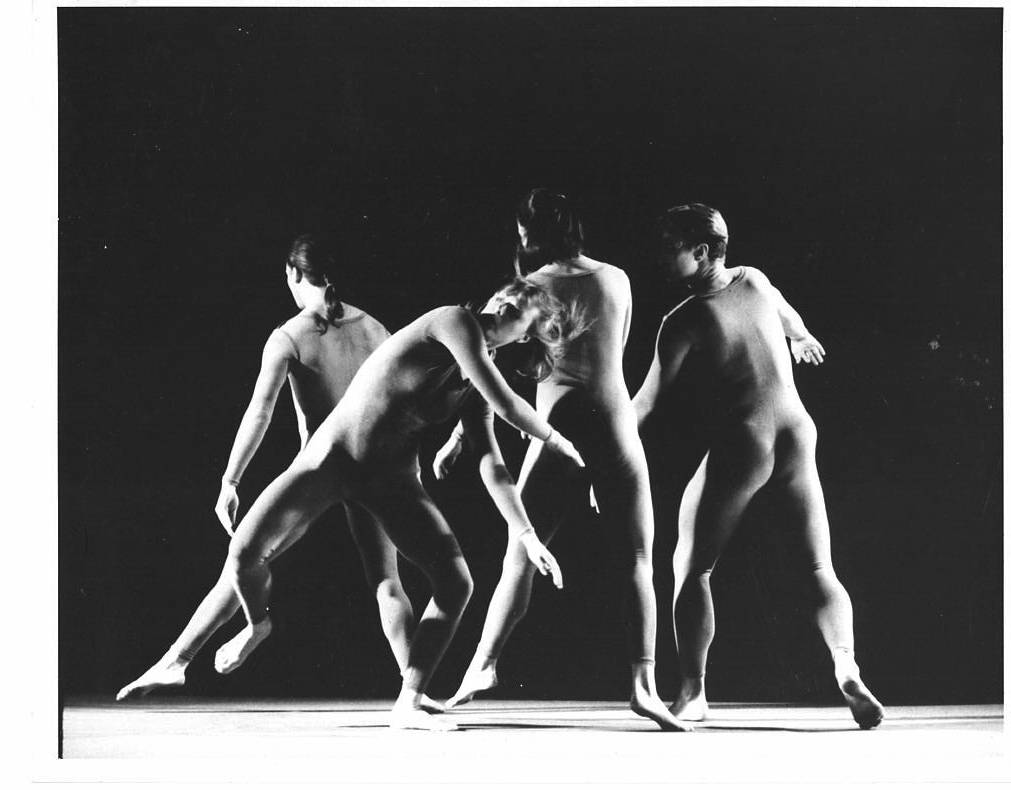

EC: During my years the dances changed intrigue substantially. I came in on Astral Convertible and the repertory of both bold macro bravado and evolving statuary-esque configurations were juxtaposed with sweeping play, carving space with delicate gestures and rocket power exuberance that sweetened, shattered, and reformed space and time. Broad visuals. Momentum, vector, and weight were central to succeeding in packed sequences. Her mechanistic interests played out as bigger choreographic movement themes while each body exploded internally with multiple tasks. Those interests, over my time, transitioned to minute, minimalist investigations that were vertical, plodding, slow trajectories with small hives of activity intersecting in nooks. For example, One Story as in Falling: as a dancer the work moved into the realm of upright mechanistic isolations within the body. A significant moving away from the quicksilver, risky off-upright axis—internal messaging that wrote surprises on the body and across the space, forcing precise, fast, and sometimes sustained intimacies between dancers. It was slowed down, cleaner, more geometric phrases and articulations.

Q: What stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today?

EC: The legacy for me is the command and freedom that’s automatic even now twenty years later—the ability to be so precise and given to abandon simultaneously, to control a party, rolling it through me articulating as much or little of it I desire to, at whim. From the simplest act—walking, turning my head to look at something—the possibilities of what it could lead to are endless. Whether I follow them through or not, even if I just continue like a normal person, at any moment, what I’m doing could become something extraordinary if I prod it to life. And that is probably what I learned most from Trisha and the work. That movement can come from the mind if you decide to create that way. But with Trisha, movement, any movement, was a seduction from the unknown, an invitation to see what could/would happen if.

Of course the work is then harnessed into repeatable crafted decisions, relentlessly in fact, more refined and precise than any other form I’ve ever danced, including ballet. But its full-on agreement with “how things work” permitted an alternate engagement that was very satisfying. Trisha was extremely intellectual and yet so playful. The internal prediction without calculation that her work demands of the dancer translates into a confidence, freedom, and joy of being alive in one’s body and knowing your options are nearly limitless. When I look back on the years and the dancing, my body feels happy in what it did. The imprint remains alive and I can still feel myself soaring through space and wriggling through sequences, being handled and trusted by my fellow dancers, trusting and handling them, in these poignant tendernesses and dependencies of the choreography between us. And of course, looking back on my youth, I get to smile and think, “Dang, that was extraordinary—my everyday normal, meaning being in service to Trisha and her work, was dance history unfolding. That’s wild.”

Elizabeth Carpenter was an original member of The Joe Goode Performance Group, and retired from The Trisha Brown Dance Company in 1995. Today she is a leader in the field of Acupuncture & Alternative Medicine. She maintains a private practice in Manhattan, teaches medicine at the graduate level, and speaks to medical and lay audiences around the nation.