“Peter and I see the Baroque and the postmodern as these sort of bookends that relate to each other, are in conversation with each other over the arc of 300 years.”

Megan Bridge and Peter Price, artistic directors of <fidget>, were invited by Andrew Repasky McElhinney to select a film to screen at Andrew’s Video Vault, McElhinney’s long-running film series. They chose to screen Trisha Brown’s staging of Claudio Monteverdi’s Baroque opera L’Orfeo (Orpheus) from 2006. Brown’s hypnotic choreography walks a fine line between dance and theater, and creates overarching patterns and structures that sweep through the entire ensemble of performers. A total symbiosis of music, text and movement. The screening is March 10 at 8pm at the Rotunda, 4014 Walnut Street in West Philadelphia. Free. 170 minutes.

We caught up with Megan, herself a choreographer and performing arts programmer, to ask her thoughts about L’Orfeo and why she chose to screen it.

Tell us about the event.

Megan Bridge: We’re screening L’Orfeo at a free film series in West Philly called “Andrew’s Video Vault.” Andrew Repasky McElhinney, an experimental filmmaker and very close friend, has been running the video vault for thirteen years and has only recently started to invite guest curators to select films for screening. Peter and I will be giving a very brief introduction to the film, talking about its context and why we chose it.

What made you choose L’Orfeo over others?

Megan Bridge: Peter and I are really interested in opera as a form, as Gesamtkunstwerk. But opera today is hard in a lot of ways. We are so used to the frameworks, in contemporary culture, of postmodernism and the distance it creates between subjects and their emotions. For experimental artists, an emoting subject is somewhat laughable, and a lot of opera is all about this. But listening to Baroque opera is a really different experience from listening to opera that came later: Monteverdi’s work, and in particular L’Orfeo, really ushered in the operatic form. In the Baroque, art was so tied to structure and formula, and the “stories” were so allegorical and poetic, almost to the point of abstraction. Then opera evolved over hundreds of years, becoming more and more overblown, dramatic, and tied to narrative. At the same time there was the rise of ballet, which often appeared in opera of course, and romanticism. Modern dance finally showed up on the scene in the early 20th century, sprinkling on a few decades of angst-ridden narrativity with Martha Graham leading the way—don’t get me wrong, I love Graham! Trisha Brown and her postmodern cohorts in the 1960s, following Merce Cunningham’s lead of course, were like a breath of fresh air! Peter and I see the Baroque and the postmodern as these sort of bookends that relate to each other, are in conversation with each other over the arc of 300 years, in the sense that they are both dealing with abstraction and have the same impatience with narrativity. This production of L’Orfeo, with Brown’s postmodernism rubbing up against Monteverdi’s Baroque, is an amazing way to get a real sense of that relationship.

What is the job of a choreographer in an opera and how does Trisha Brown play with this form?

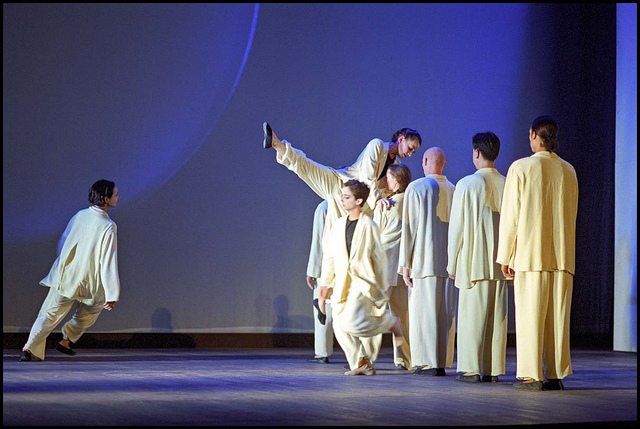

Megan Bridge: The role of the choreographer in opera is really different depending on the opera and the production. Often the choreographer is just in charge of the full-on dance sections in an opera, and the director is in charge of the movements of the singers and the overall movement and blocking of all the performers throughout the work. In L’Orfeo Trisha Brown has both the choreography credit and the director credit. I love it when opera companies bring in dance-based practitioners to both choreograph and direct, because they are able to bring a different perspective to the whole work. You can really see this in Brown’s L’Orfeo. The dancers aren’t just eye candy, brought in to give the audience a little entertaining break. And the singers don’t just stand around and wave their arms while they sing, relying on the dancers to bring a more kinetic presence into the work. Every time they are on stage, the singers are performing task-based choreography, for example: simple but precise hand and arm gestures, standing completely still and neutral but with a particular facing and on a particular spot, or walking on time to the meter while weaving in and around the other performers in a specific pattern. When the dancers are on stage they join as members of the ensemble. Their choreography is more complicated, involving partnering, weight sharing, etc. But the singers really rise to the challenge…leaping, going to the floor, and really getting fully physically invested in the work. All the performers, not just the dancers, are barefoot. For the entire opera Brown is really blurring the distinctions between the singers and dancers, and this is really satisfying to see.

Why does the opera and Brown’s choreography work for you?

Megan Bridge: What makes this opera work for me is the way the task-based movement and the abstraction of the libretto reveal this really simple humanity. When the messenger comes to tell Orpheus that Euridice is dead, the libretto simply says:

Messenger: Your wife is dead.

Orpheus: Oh woe is me.

It’s so non-emotive it’s almost ironic. And while the performers are singing these lines, Brown gives them these really simple gestures to do—no overblown heart-clutching or fake crying. The simplicity of the gesture and the libretto work together to leave room for the performers to be themselves. The work really comes alive through the deep investment of the performers as they carry out their tasks, weaving together the complicated tonal and rhythmic structure of the music and simultaneously performing Brown’s movement. There’s no room or time for overblown embellishment. There is concentration, commitment, and deep investment: both the singers and the dancers of the Trisha Brown Company exist so exquisitely as themselves inside of Brown’s movement. The choreographic approach very much reminds me of David Gordon, another post-modern choreographer from the Judson Dance Theater era, who, when I worked with him on a project in 2014, made us carry our scripts in particular ways in order to prevent us from unnecessary gesticulations or physically “over-acting.”

Having created your own dance work from Robert Ashley’s opera Dust, are there specific elements of the choreography that really stick out for you?

Megan Bridge: I love the way Brown maps bodies in space, the way she uses the bodies as a “chorus,” not at all to act out the narrative but simply to provide a structure which houses the narrative. Her choreography is spacious and abstract, allowing narrative to arise in relation to the libretto, the music, or the movement, but not forcing narrative on any of them.

Megan Bridge is a dancer, choreographer, curator, and dance writer. She currently co-directs <fidget>, a platform for her collaborative work with sound artist Peter Price. <fidget> has toured to New York, Berlin, Vienna, Zurich, Dresden, Arizona, and Johannesburg. In 2009, Bridge and Price founded thefidget space, a hub for research and experimental performance which has hosted dozens of local, national, and international artists. Bridge has worked as a dancer with choreographers and companies such as Group Motion, Jerome Bel, Lucinda Childs, David Gordon, Susan Rethorst, and Willi Dorner, and has studied with Deborah Hay, Xavier LeRoy, Jan Fabre, and Miguel Guittierez. She is the executive director of thINKingDANCE.net, where she also writes and edits, and she has published articles in Dance Chronicle, Dance Magazine, and Pointe Magazine. She holds a BFA in dance from SUNY Purchase, and lives in a warehouse in Kensington, Philadelphia with her husband and two kids. www.thefidget.org