“With Trisha, movement, any movement, was a seduction from the unknown, an invitation to see what could/would happen if. “

Elizabeth (liz) Carpenter was a dancer with the Trisha Brown Dance Company from 1989 to 1995.

Elizabeth (liz) Carpenter was a dancer with the Trisha Brown Dance Company from 1989 to 1995.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work?

Elizabeth Carpenter: I was dancing with the Joe Goode Performance Group in San Francisco, and a dancer friend of mine said Trisha Brown Company was in town and auditioning. My friend wanted to audition and asked me to go with her. So I did. I fell in love with the strange interdependency/contingency physicality of it—unlike anything I’d ever done before. It was a new physical conundrum to master and it felt exhilarating. They hired me and brought me to New York. Leaving Joe, having been an original member of his company, was a hard decision, but I couldn’t resist what I’d experienced at that three-day audition. Of course I’d heard of Trisha Brown, but had never seen the work before. I saw the company perform for the first time that weekend. I remember thinking, “It sure doesn’t look as complex as it feels.” I was hooked, and remained hooked, as the repertory took me through numerous stages and refinements of the interdependency/contingency dynamic.

Q: What were rehearsals like?

EC: I guess I would say that like the finished product, rehearsals were meticulous, and relentless in perfectionism that somehow yielded playful exploration. The most challenging thing to master was related to older pre-your-era works where the reproduction of an originator’s idiosyncrasies was required. Videos of rehearsals when works were being created were used to pass repertory through generations. Separating peculiarities of an individual from the choreography was no easy feat. The natural connection was the material itself. It was like swimming. You and the water are one, and you’re both predictable and unpredictable simultaneously. And yet, you know—without knowing—how to do it.

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be and why?

EC: Lateral Pass, because it’s so whacky and joyful and exhausting and every dancer gets to shine gloriously.

Q: How did Trisha’s dances evolve during your time with the company?

EC: During my years the dances changed intrigue substantially. I came in on Astral Convertible and the repertory of both bold macro bravado and evolving statuary-esque configurations were juxtaposed with sweeping play, carving space with delicate gestures and rocket power exuberance that sweetened, shattered, and reformed space and time. Broad visuals. Momentum, vector, and weight were central to succeeding in packed sequences. Her mechanistic interests played out as bigger choreographic movement themes while each body exploded internally with multiple tasks. Those interests, over my time, transitioned to minute, minimalist investigations that were vertical, plodding, slow trajectories with small hives of activity intersecting in nooks. For example, One Story as in Falling: as a dancer the work moved into the realm of upright mechanistic isolations within the body. A significant moving away from the quicksilver, risky off-upright axis—internal messaging that wrote surprises on the body and across the space, forcing precise, fast, and sometimes sustained intimacies between dancers. It was slowed down, cleaner, more geometric phrases and articulations.

Q: What stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today?

EC: The legacy for me is the command and freedom that’s automatic even now twenty years later—the ability to be so precise and given to abandon simultaneously, to control a party, rolling it through me articulating as much or little of it I desire to, at whim. From the simplest act—walking, turning my head to look at something—the possibilities of what it could lead to are endless. Whether I follow them through or not, even if I just continue like a normal person, at any moment, what I’m doing could become something extraordinary if I prod it to life. And that is probably what I learned most from Trisha and the work. That movement can come from the mind if you decide to create that way. But with Trisha, movement, any movement, was a seduction from the unknown, an invitation to see what could/would happen if.

Of course the work is then harnessed into repeatable crafted decisions, relentlessly in fact, more refined and precise than any other form I’ve ever danced, including ballet. But its full-on agreement with “how things work” permitted an alternate engagement that was very satisfying. Trisha was extremely intellectual and yet so playful. The internal prediction without calculation that her work demands of the dancer translates into a confidence, freedom, and joy of being alive in one’s body and knowing your options are nearly limitless. When I look back on the years and the dancing, my body feels happy in what it did. The imprint remains alive and I can still feel myself soaring through space and wriggling through sequences, being handled and trusted by my fellow dancers, trusting and handling them, in these poignant tendernesses and dependencies of the choreography between us. And of course, looking back on my youth, I get to smile and think, “Dang, that was extraordinary—my everyday normal, meaning being in service to Trisha and her work, was dance history unfolding. That’s wild.”

Elizabeth Carpenter was an original member of The Joe Goode Performance Group, and retired from The Trisha Brown Dance Company in 1995. Today she is a leader in the field of Acupuncture & Alternative Medicine. She maintains a private practice in Manhattan, teaches medicine at the graduate level, and speaks to medical and lay audiences around the nation.

As part of Trisha Brown: In the New Body, drawings, writings, and other works by Trisha Brown and her collaborators—including by Robert Rauschenberg, Elizabeth Murray, and Nancy Graves—are displayed in an exhibition organized by Bryn Mawr College’s department of Special Collections. Trisha Brown: (Re)framing Collaboration An Exhibition of the Art of Trisha Brown and Her Collaborators opens a window on how the visual arts informed Brown’s choreography, and presents drawings and paintings that stand on their own as works of artistic expression. Curators Brian Wallace and Matthew Feliz shared their thoughts in a quick interview on their thinking behind the exhibition.

Q: What do you find compelling about Brown’s drawings?

Q: What do you find compelling about Brown’s drawings?

Matthew Feliz: I’m fascinated by the ways in which Brown’s approach to drawing evolved over the course of her career and in relation to her choreography/dance. I found the drawings that she did in the early 1990s to be particularly compelling—drawings that grew out of her sustained engagement with the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. The visual traces of her markmaking record acts of intuition and improvisation, responses to and investigations into Bach’s highly complex musical structures—repetition, theme, and variation.

Brian Wallace: Brown’s visual works illuminate her methods and insights in the realms of choreography and performance, but they don’t need that connection to be meaningfully expressive. They embody acts of exploration and resolution in ways that are inherent to visual art—they visually link formal and narrative problems and solutions; they pose a spectrum of issues ranging from the personal to the profound, and they span ancient and contemporary procedures of representation while they reveal Brown’s parallel investigations and conclusions in movement and space.

Q: Are there some common threads, from her collaborators’ art and artistic sensibilities, that you strike you in a way as to think, well, of course they became collaborators?

Brian Wallace: Brown, Robert Rauschenberg, and Laurie Anderson—the artists whose works I know best—are all selective, even attenuated, but nonetheless voracious engagers with and redeployers of the whole panoply of visual culture. They strike me as passionate and knowing quoters and borrowers, as exuberant but not unreflective cutters and pasters, and as instructively divergent representatives of post-modernism. Too, their image of the body is a fascinating palimpsest.

Matthew Feliz: We included a couple of photographs by Babette Mangolte that document two of Brown’s early performances. These works gesture rather tantalizingly towards the intersections of communities of dancers/choreographers/performance and experimental filmmakers during the 1960s and 1970s.

Brian Wallace: The intergenerational aspect of the exhibited collaborations—and these artists have engaged in many other birth-year-diverse projects – is also noteworthy: these artists, at quite different moments in their respective careers, generously, carefully, and ambitiously offered and took inspiration from one another.

Q: How did you go about selecting work for this exhibition, what were you looking for?

Brian Wallace: We—Matt, Lisa Kraus, and I—wanted to find works that would illuminate Brown’s working methods, attract and engage a visual arts audience and a performance-oriented audience, and give the members of those audience some category problems as well as some information to mull over, hopefully with one another—and, ideally, with students. So, groups of works keyed to performances audiences will experience as part of the larger Brown project; sets of works in completely different media that share clear affinities; an arrangement of works that show Brown’s expressive and intellectual range.

Matthew Feliz: The works selected, photographs of Brown’s early career (late 60s to early 1970s) and her drawings and prints by other artists, allowed us to create both a chronological structure and a set of thematic groupings that situate Brown’s drawings within the broader context of her own dance practice.

Brian Wallace: The intimate scale of the gallery was used to intensify the impact of Brown’s works: the varied viewing dynamics of video/audio material, large-scale drawing, small notes capturing fugitive thoughts, and dense, compact explorations of knotty procedural problems were carefully considered when the list and location of the works was reviewed and finalized.

Trisha Brown: (Re)framing Collaboration, An Exhibition of the Art of Trisha Brown and Her Collaborators continues until December 11 at Bryn Mawr College, Canaday Library, Class of 1912 Rare Book Room Gallery, 101 North Merion Avenue, Bryn Mawr, PA 19010. Open daily 11am–4:30pm. Free.

“She made excellent art for decades. That’s worth remembering.”

Hope Mohr was an apprentice and then company member with the Trisha Brown Dance Company from 2001 to 2005.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work?

Hope Mohr: I first saw Trisha’s work when I saw Mariah Maloney perform Trisha’s solo Rage and the full company perform Groove and Countermove in a summer outdoor festival in downtown Manhattan. It was distinctive movement, and a compelling combination of the abstract and the personal. Soon thereafter, I began taking classes at the studio in 2000. I was coming from a different kind of dance training at the Merce Cunningham studio. I was fascinated by the idea of doing less—muscularly—than I was used to, but being nonetheless specific. It was the first time I lay down on the floor to prepare for movement. I became fascinated by finding specificity from a released place. I was compelled by the challenge of coming to the work from a more conventional dance training background. I had to unlearn dance as shapemaking and relearn dance as falling.

Q: What were rehearsals like?

HM: When I started working with the company, it was a lot of learning repertory. I had the privilege of working closely with Abby Yager and Mariah Maloney. Cori Olinghouse and I were hired at the same time, so Cori and I spent a lot of time together. That was fun. I worked on embodying the values of weight, sequence, and precise pathways. I loved the sensuality of the movement and the freedom that the work’s abstraction gave me as a performer. I enjoyed applying Alexander Technique to the repertory. One of the first roles I learned was Trisha’s part in Set and Reset. I felt honored and intimidated to be doing the part. It remained my favorite part to do during my whole time as a company member. I don’t think I’ve ever had as joyful an experience as performing that part.

Q: How did Trisha create work on the dancers?

HM: I didn’t participate in the making of new work until Trisha made how long does the subject linger at the edge of the volume. It was a motion capture piece. Trisha would create scores for action using phrase material that created managed chaos in the room. She would develop rich phrase material and then map it onto space using improvisational scores. As a writer, I also connected with the distinct language of the company in rehearsals. Movement was a set of impossible tasks: “fall without curving,” “slosh the arms to move the body up,” “find a crackling rhythm,” “toss your head like a horse.”

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be and why?

HM: Set and Reset. It’s elegant, sensual, complex, and fun.

Q: What stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today?

HM: Trisha’s work offered a physical practice of dance as falling, rather than simply shapemaking. I think that physical practice is a metaphor for how Trisha approached dancemaking. She modeled a commitment to endless inquiry and radical experimentation. In my own work, I continue to be inspired by her intellectual and physical rigor. Also her resilience. She made excellent art for decades. That’s worth remembering. There are so few female artists who persist over the long haul, despite the ups and downs of the field. Working with her was an incredible gift.

Hope Mohr is currently the artistic director of Hope Mohr Dance.

“When I watched Trisha dance, be it on video archived early works or watching her do If you couldn’t see me from the wings, no matter what ‘form’ it was she was attempting, I saw how personal it was for her.”

Choreographer, dancer, and teacher Stacy Spence was a dancer in the Trisha Brown Dance Company from 1997 to 2006. He currently teaches classes and direct restaging projects for the company.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work?

Stacy Spence: I remember seeing just a short video clip of Set and Reset in college while in Denver, or maybe at the Colorado Dance Festival—someone showed a video around that time. I had never seen such a fluid way of moving and staging before and was immediately drawn to it. I had always felt like I was more of an individual kind of mover, and not so great at moving like I was suppose to in classes. Seeing that dancing struck a chord, it looked like unknown and individualistic movement to me. Having said that, I almost felt as if I knew that movement already. It was few years later, when I moved to New York, that someone suggested that I might be a good fit for Trisha’s work. The company was elusive during this time, they weren’t in town much, but they gave periodic workshops and I took one. That is where I got to connect my idea of the work from that short video clip to the actual physicality of the work.

Q: What were rehearsals like?

SS: I had danced with some independent choreographers project to project before joining the company. So working with a group day to day and getting to know and create with each other over a long time was something that I wanted to experience. We would usually work with Trisha on building new material, or work on learning and keeping up repertory.

Q: How did Trisha create work on the dancers?

SS: Depending on what was needed for the work, Trisha might ask a few of us to come in and be with her while she made new material. We would shadow her as she worked out ideas and distilled those ideas to what was essential. Then the conversation would begin, between what you saw her do and helping get it down, or she might be interested in where you might take that idea. At other times, she might throw out an idea and see how we interpret it and manifest that idea. I remember is being asked to move like the sound of a whistle, while we were making the Scherzo section in 5 Part Weather Invention. Things like that tickles a person’s creative spirit. I loved that improvisation was important in the making of work. Parts of all of us are in the repertory. Trisha’s genius directing of course, but I can also see Diane, Carolyn, Wil, Lance, Keith, Kathleen, Ming, Abby, Brandi, Cori, and all the other dancers I got to be with, all of them bubbling about, contributing to Trisha’s vision.

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be and why?

SS: Oh no, only one! I have always been so fond of For MG: The Movie. Something about the use of time in that piece, gives me space for imagining things happening beyond the piece. No, wait . . . Newark, to stay challenged. I can do this. Wait ,wait . . . Set and Reset, first thing I ever saw. I am cheating.

Q: How did Trisha’s dances evolve during your time with the company?

Q: How did Trisha’s dances evolve during your time with the company?

SS: As I think on my experience of learning through the cycles of dances, I feel that ideas would keep being layered upon from the last pieces. So works I was part of would have elements from what was learned in previous cycles mixed into what was needed for forms in the current dance. When I joined the company, Trisha was well into the Music Cycle and making the opera L’Orfeo. So with music, there was the added complexity of Trisha’s choreographic structures and her choices with the musical structures of the composers.

All of this layering was challenging as a dancer, which is fantastic. We all have aspects that we are comfortable with, are good at, or naturally come to us. But that layering of complexity means you come up against aspects that may not be your strong suit, that you may not be as confident about being able to manifest. That is a challenge, but it is also exciting to meet that challenge.

Q: What stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today?

SS: Something that I have gleaned through dancing, teaching, and sharing Trisha’s work is an idea of: the simple in the complex and the complex in the simple. As I think of Trisha the person—when I watched Trisha dance, be it on video archived early works or watching her do If you couldn’t see me from the wings, no matter what “form” it was she was attempting, I saw how personal it was for her. I saw the person. I saw the human. That is what I carry with me and what I connect to most.

Photos: Stacy Spence dancing in Set and Reset (c) Naoya Ikegani Saitama Arts Foundation 2006. Photo of Stacy Spence courtesy of the artist.

“Almost nothing in my modern dance training prepared me technically for the movement vocabulary Trisha was developing.”

Elizabeth Garren danced for (and with) Trisha Brown from May 1975 through December 1979.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work? And was that when you first connected with her work?

Elizabeth Garren: When I visited New York City for two months in 1973 to study dance and attend performances, I was surprised it was Trisha’s relatively non-dance work that most captivated me—think Trisha and Sylvia Whitman doing Pamplona Stones in her loft. I was taken with her stark creativity, elegant tempo, and droll humor. I was somewhat prepared for her style from Grand Union performances in Minneapolis, but surprised how her work stood out to me compared to everything else I saw in New York, like a sharp knife cutting through fat.

When she brought her company to the Walker Art Center in 1974, I volunteered to be the extra dancer they needed for their performance there. After that night’s show, I showed the company a jolly good time, walking them to dance at a biker bar through an abandoned railroad lot near my home—we got halfway there before they demanded to return home asap, where we danced to Stevie Wonder and Aretha. That next spring, Trisha phoned me in Minneapolis to ask if I’d be willing to move to New York City asap as she was gathering together a new company. Wow. I arrived fresh off the train with my duffle bag, took the elevator up to the 5th floor of 541 Broadway and launched into learning a piece called Locus, which we would perform in a loft showing three weeks later. (Idol Yvonne Rainer watching!) Almost nothing in my modern dance training prepared me technically for the movement vocabulary Trisha was developing. At least I was well versed in improvisation, in movement as well as life.

Q: What were rehearsals like?

EG: Exit the elevator, Ginger’s long toenails clicking over for a proper wiggly greeting, dumping my stuff, lying on the floor to contact the part of me I would need for the hours of dancing ahead: availability of every joint of my body, a dropping away of all my dance technique from the past, a sense of multidimensional awareness visually/spatially to master unison movement with no outward musical tempo, trying to match my “heft” with Trisha’s. At the time, all of us did Elaine Summer’s ball work, informally, individually, checking in verbally as we rolled around. Very little, if any, transition to standing and dancing.

With Locus, she handed already created movement to us, then asked us to make improvisational choices about where to take the movements spatially on the marked floor grid, with whom to join up in unison, when to break apart from unison etc., which made the piece come alive for us and required total presence of mind. Later, Solo Olos was to require even more such mental aliveness, especially for the “caller,” Mona Sulzman. And in Line Up, how about precisely capturing five- to ten-second chunks of freely improvised moments of lining up, getting five people to agree on exactly what, when, and where it had just elusively happened, then rigorously setting it in stone for the ages? Each time we prepared to perform Line Up, Trisha became the nitpicker from hell, knowing the piece could dissolve into sloppy, rather then precise, casualness. We hated those rehearsals, maybe Trisha did too. Drudge work, but she knew how to make the jewelry shine.

Q: How did Trisha talk about the work to you?

EG: If Trisha talked about the work at rehearsal, it was focused on the practical task at hand, not conceptual or the bigger view. Looking back, she had to patiently work to divest me of my tendency to add too much expression to my movement. I had been trained to project to the last row in a theater, often being asked to smile or look like I was having fun. Oh boy. Settle down, Elizabeth.

Q: What was, for you, most challenging to master?

EG: What was challenging to master was dancing anywhere near as good as Trisha, and as I said, in unison with her. I remember the first time I was able to match the timing of Trisha’s “squat to scoop, rise, and fall into anther squat” move in Locus. It was not from watching her and controlling my tempo with muscles as I had before, but from finally feeling myself as Trisha seemed to feel herself . . . the deepness of her hip fold, her untrapped pelvis, the comfort with falling taking its own time, no rush, no fuss, just the uncluttered presentness of this, then that, continuing, then continuing some more.

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be?

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be?

EG: This may surprise you, but it would be Locus as danced to Al Green’s “Simply Beautiful.” And I would be doing it with Trisha, Judith, and Mona, as we did in one of our first (1975) residencies, on the grounds of Art Park, in a hot breezeless tent, with the odd groups of tourists wandering through our rehearsals, many asking, “Is this yoga?” The heat must have gotten to Trisha because she uncharacteristically asked us to play some Al Green songs as we ran through it again. As rigorous and relatively undynamic as Locus is, it is rich and body friendly to dance. But when the lazy back beat of the Reverend came on, it took Locus to the moon—which is kind of like an island. Up till then we had danced only in silence. Now for a few minutes we let go of all rigor and danced the boundless heck out of Locus. Mmmm, mmm. (more…)

Trisha Brown: In The New Body from Byron Karabatsos on Vimeo.

“I also have been most moved by Trisha herself. She is a women filled with integrity and honesty and directness. Knowing her has changed the way i hold myself as a human being.”

Judith Ragir danced in Trisha Brown’s company in the mid-to-late 1970s.

Judith Ragir danced in Trisha Brown’s company in the mid-to-late 1970s.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work?

Judith Ragir: I saw Trisha first in the Grand Union at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Seeing the Grand Union free improvise really changed my artistic life. I came to New York after that to study. I was planning on being a choreographer myself and I just wanted to learn from the New York dance scene in the late 70s. Trisha was teaching an improv class in her studio during the fall which I attended. Little did I know that she was using that class as an audition. When it was done she invited Mona Sultzman and I into her first “dance” company—before that she had mostly done equipment pieces and pedestrian movement choreography. When she asked me to be in her company, she mentioned that she was also inviting Elizabeth Garren from Minneapolis into the company. I had a good laugh. Elizabeth and I had been very close friends in Minneapolis, prior to my moving to New York City! What a coincidence and a blessing. I could continue to dance with Elizabeth.

Q: What were rehearsals like?

JR: When this first “dance” company began, Trisha did not know whether other dancers could dance her movement. So we were really quite an experiment. I was taught in the Wigman style of space, time, and energy and improvisation and I think that actually helped me to observe and copy her movement. We all took release work from Elaine Summers next door so that we would be free enough to move like Trisha. We worked in Trisha’s home loft every day and worked hard. We learned Locus and Primary Accumulation first. Then we made Line Up by improvising for twenty seconds and then remembering what we did. That was a blast. Occasionally we made our own movement phrases but i think mostly we learned her movement backwards and forwards and upside down! Also, almost all the work I performed in was danced in silence.

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be and why?

JR: I left the company before Trisha really started moving through space which was a real shame for me. I left too soon in my arrogant eagerness to do my own work. But I loved Locus. It was the closest to jazz improvisation, which I adored, that the dance world had seen up to that time. I also loved a section we called “humming” which was very small, delicate, pedestrian movement all done in a close knit clump in the front center of the stage. Gorgeous.

Q: How did Trisha’s dances evolve during your time with the company?

JR: For me, the four years or so right after I left were the most exciting. Seeing her start to move in space and making pieces like Opal Loop, Set and Reset, and Glacial Decoy.

Q: From your close interaction with Brown, what stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today?

JR: Learning to move organically with both smoothness and accents. Learning to get out of “performing for the audience” and just being a body in space moving. I have never moved as brilliantly since, and the movement was not exactly “technical” like you would learn in dance class. (Although now I understand that some “Trisha Brown Style” is taught and copied everywhere.) It was total body movement and free joyous joints. Unfortunately the current “Trisha Brown Style” seems to miss what was most innovative about her movement but so be it. Its quirkiness, its accent, its unpredictableness, for example. I also have been most moved by Trisha herself. She is a women filled with integrity and honesty and directness. Knowing her has changed the way i hold myself as a human being. She was not easily pushed around by fashion and yet she had to hold herself upright in the face of so much pressure and responsibility. To this day I feel this personal influence very strongly.

JR: Learning to move organically with both smoothness and accents. Learning to get out of “performing for the audience” and just being a body in space moving. I have never moved as brilliantly since, and the movement was not exactly “technical” like you would learn in dance class. (Although now I understand that some “Trisha Brown Style” is taught and copied everywhere.) It was total body movement and free joyous joints. Unfortunately the current “Trisha Brown Style” seems to miss what was most innovative about her movement but so be it. Its quirkiness, its accent, its unpredictableness, for example. I also have been most moved by Trisha herself. She is a women filled with integrity and honesty and directness. Knowing her has changed the way i hold myself as a human being. She was not easily pushed around by fashion and yet she had to hold herself upright in the face of so much pressure and responsibility. To this day I feel this personal influence very strongly.

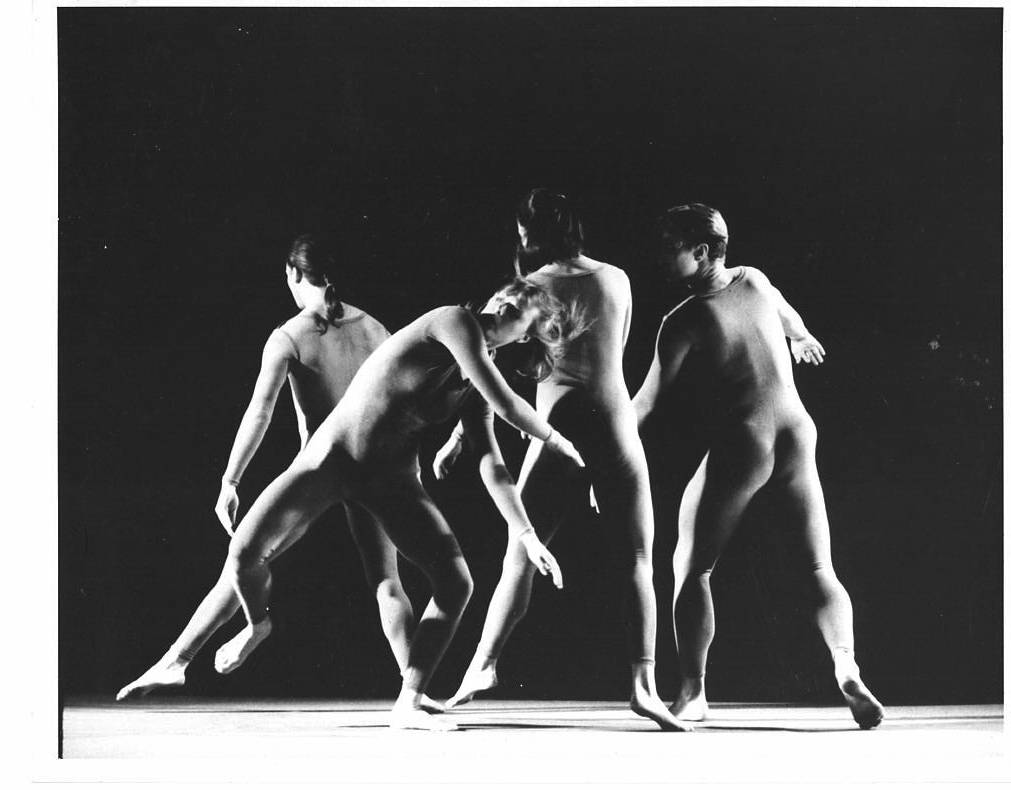

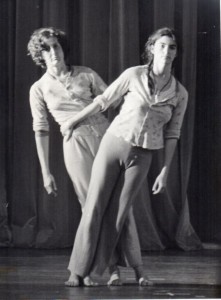

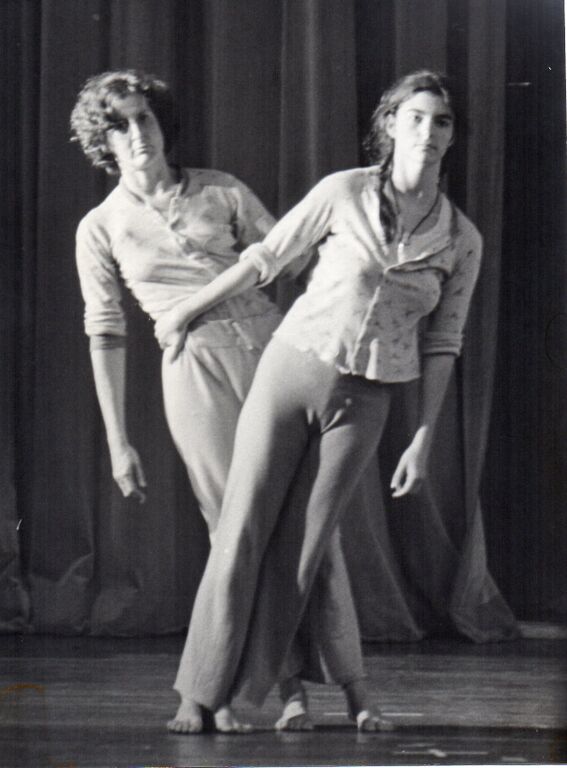

Top photo: Judith Ragir, photo by Tim Francisco. Bottom photo: Dancing with Trisha Brown, photo by Babette Mangolte.

“Upon meeting Trisha, I felt a tremendous permission to get dirty and play with movement. She was totally open and made gasping noises when something beautiful happened in the studio.”

Laurel Jenkins Tentindo danced for Trisha Brown with Trisha Brown Dance Company from 2007 to 2012. She continues to work with the company by restaging works and occasionally performing with them.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work?

Laurel Jenkins Tentindo: I first encountered Trisha Brown’s work as a dancer. Iréne Hultman, a former Trisha Brown Dance Company dancer, was a visiting professor at Sarah Lawrence College. She introduced Trisha Brown’s basic movement principles to me within her own sensual, spunky, choreography. I loved the mix of specificity, which I enjoyed exercising from years of ballet, and freedom as I was in the process of exorcising years of ballet. Iréne’s approach felt jazzy, feminine, powerful, and playful all at the same time. I was totally captivated by this new way of moving. I loved learning how different joints could initiate a sequence of events in the body. I remember practicing what I learned in Irene’s class on a rooftop in San Francisco—before I knew about Roof Piece.

Q: What were rehearsals like?

LJT: Trisha started working with me once I joined the company. I was involved in making a really difficult partnering section for L’ Amore with Jin, Mindy, and Todd. We were fearless and made movements called things like “the dragon.” I loved dancing with Jin because he was so strong and willing to take risks. I was safe upside down and twirling with him as my partner. Trisha asked us to fly across the room. We did.

Upon meeting Trisha, I felt a tremendous permission to get dirty and play with movement. She was totally open and made gasping noises when something beautiful happened in the studio. That is how we knew we should repeat it. It was thrilling.

Q: What kind of conversations did you have?

LJT: Trisha and I were in a conversation about the art of puppetry. She asked a group of my puppet friends to come into the studio—and we did a three-person puppetry sequence with a bunraku puppet made by Luis Tentindo. It was so fun to see Trisha’s choreographic interests manifested in the puppet. The puppet could do anything partner-wise and never go tired. We never did work with the puppet beyond this rehearsal—but I think we both enjoyed thinking about dance as a moving sculpture—and that partnering was a kind of enormous architecture for humans to traverse.

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be and why?

LJT: Right now it would be Opal Loop, because I am dancing it at the moment and love the phrases. Learning this piece cracked a Trisha Brown code for me in terms of dynamic and deep movement intention within the phrase material and group forms. I watched the Crosby St. performance each night before I performed this piece, and I was inspired by Trisha’s timing! She was totally wild! Her role was so wonderful to dance because she was an instigator, always staring trouble!

All the early stage pieces are high on my list including Glacial Decoy and Set and Reset. The movement feels good. These two works both have intricate phrase material and very clear spatial group forms that contrast and contain the wild individuals. I love this balance—it feels very supportive to be inside this kind of work.

Q: From your perspective, physically, artistically, how did Trisha’s dances evolve during your time with the company?

LJT: I was involved in the final four years of Trisha’s making career. I feel honored to have participated in making the twilight pieces. Iréne called the last phase of her work, “the music cycle”—when she was working with operas. Additionally, there was a tremendous amount of partnering in the last works. In the two Rameau operas I helped build, Trisha was also interested in a baroque gestural quality. Hands swirled and wrists circled. People spiraled around each other. In making the operas, I became fascinated with how nonliteral movement vocabulary existed within a literal text/story (of the opera). At one moment in L’Amore I became an archer—and this image dissolved into partnering. I wondered if it was possible for literal imagery to appear and disappear in and out of abstract movements. I recently made a piece in Los Angeles called wind hill that deals with this question.

![IMG_5020 [800x600]](http://trishabrown.blogs.brynmawr.edu/files/2015/10/IMG_5020-800x600-300x200.jpg) Q: What stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today?

Q: What stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today?

LJT: Strangely, Scallops has stayed with the most. I am so surprised by this because I thought the piece was boring at first. The Early Works have totally captivated my attention. This one in particular traces the perimeter of the space and allows each dancer the agency to choose who they pivot around. Each scallop lands on the edge in unison and all the dancers “pivot” together. I love the idea of a rule game dance. I love how establishing a set of parameters creates a living puzzle, one where the dancers have the power to compose within. In this way the Early Works within Line Up have a revolutionary intention—the genius role of the choreographer gives way to the intelligence of the group. I see the dancers as one thinking body—and the dance being the organizing principle.

Secondly, I am inspired by Trisha’s rich movement vocabulary and phrasing. Her dancing is delicious, and because I know this approach to dancing, I feel it is possible to dance for my whole life.

Photos: Roof Piece photo by Arthur Chedeville and Sticks photo by Julio Moreira.