“I think the most profound way she taught me was through osmosis—watching her, sensing her . . . dancing with her.”

Eva Karczag began learning Elizabeth Garren’s roles in Line Up and Locus, from her, in the winter of 1979. but it was in the summer of 1979, during the Trisha Brown Dance Company residency at Aix-en-Provence, that she started working with the whole company. She left the company in 1985.

On March 12, 10am–4pm Karczag will be leading the workshop Deep Dive for Philadelphia area dancers. Click here for more information. The evening of March 12 at 7pm, Karczag and Lisa Kraus share their experiences as dancers of Brown’s work through conversation and demonstration in Play and Replay. Click here for details.

Q: What was your first encounter with Trisha Brown’s work?

Eva Karczag: Prior to coming to New York in August of 1975, I was dancing with Richard Alston’s British experimental dance group Strider. Just before Richard and I left England, Strider was at Dartington College at the same time as Steve Paxton, who was teaching there. The last thing I remember Steve saying to me when we said good-bye was, make sure you contact Trisha Brown when you get to New York. Of course, I had read Yvonne Rainer’s book Work 1961–73, but I didn’t especially single out Trisha from the other dancers. However, when I got to New York, I took Steve’s advice, and called Trisha, thinking that I’d be able to take classes with her. What Trisha told me was that she didn’t teach, she choreographed. I placed Trisha on hold.

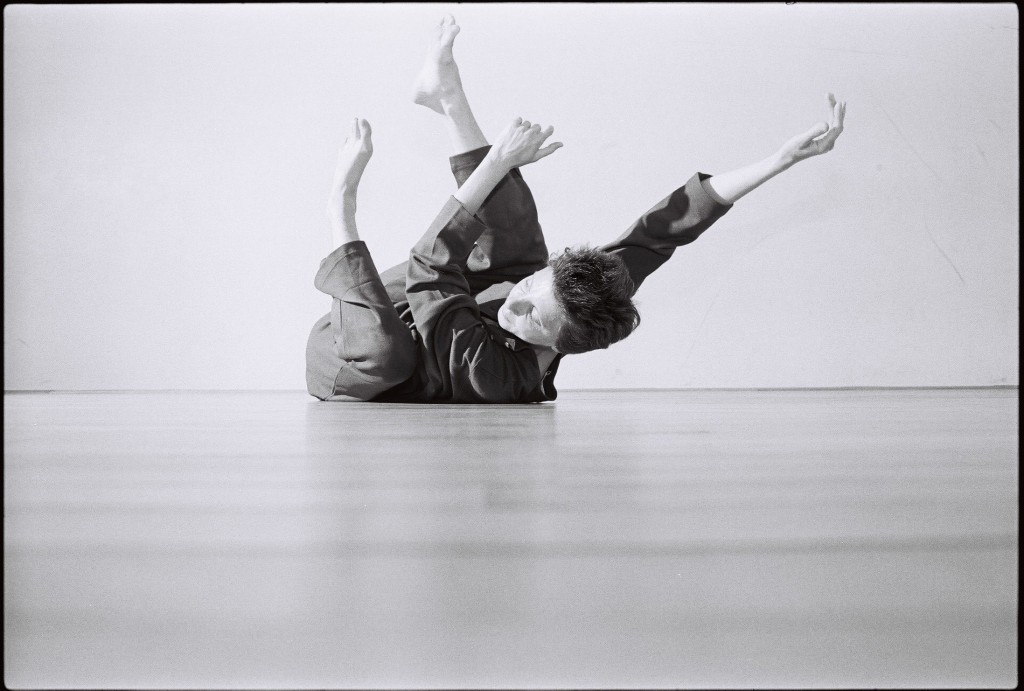

Some time during winter 1975/76, Richard Alston and I were invited to a showing of Trisha’s work in her loft at 541 Broadway. It could have been Jan 1976. There was a lot of snow. The two pieces I remember are Pamplona Stones and Locus. By that time I had been practicing the Taiji for three or four years, had taken Alexander Technique lessons for a couple of years, and had had experience with Release Technique and Contact Improvisation. I was trying to imagine where this softer, more aware and respectful way of moving in which I was immersing myself, could be taken within a dancing vocabulary, into dancing that was released, fluid, organic, and physically complex and challenging. Locus, and particularly Trisha’s dancing, was the embodiment of what I was searching for. I was blown away by the beauty of the movement I saw at that rehearsal—it flowed, had an inner drive that came from ease rather than forcefulness or excess tension. Then and there I fell in love with Trisha’s way of moving—her freedom, her flow, her quirkiness, her body intelligence and the lush sensuality of her moving, the intelligence of the rigorous structures she set in motion, the complexity and depth that so clearly lived within the unpretentious, functional presentation of her dances, and her exuberant and ever-present humor. I remember leaving that rehearsal completely ignited by what I had seen. I may have levitated home through the snowy streets, and I knew that this was the kind of dancing I wanted, even needed, to do. I wanted to dance Trisha’s dances. I wanted to dance with Trisha Brown. After that rehearsal, I went to see Trisha’s New York performances every time I could, and when Elizabeth Garren left the company, and Trisha asked me to think about whether I would like to take Elizabeth’s place, there was nothing to think over: I immediately said yes. Dancing with Trisha changed my dancing, and changed me, in profound and unceasing ways.

Q: What were rehearsals like? How did Trisha create work on the dancers?

Eva Karczag: Rehearsals were challenging, engaging, focused, and a lot of fun. Trisha taught us material and showed us how to be specific and true to the movement; she gave directions and plans of action, then gave us freedom to explore and play. We learned to aim for the best and let go of what didn’t meet expectation. She treated us as adults and I always felt respected and valued. At the time I danced in the company, Trisha was still dancing with us. I think the most profound way she taught me was through osmosis—watching her, sensing her . . . dancing with her.

When she taught us material, she would sometimes give us her image or source. This gave added flavor to a movement. She was very specific about the details of the body. Mostly I remember this information being given through showing us the material over and over.

Perhaps because my tendency is for flow, I think I understood her way of moving and her movement propositions easily. My memory is that her movement fell into my body without much effort. By the time I joined the company, I had done quite a lot of work with cutting and splicing movement material together to form pieces or events, so I enjoyed improvising with set material, which is the way we built Opal, Son of Gone Fishin’ and Set and Reset, and that, also, happened quite organically and intuitively. The challenge for me, I feel, came from the passion to excel, to dance Trisha’s dances fully and with total abandon yet with extreme precision and clarity; to be completely present and available in my dancing so that I could be multi-directionally aware within my own body, as well as towards the other dancers moving alongside me, while inviting the audience’s kinesthetic and intellectual attention.

Q: If you had one Trisha Brown dance to take with you to a desert isle what would it be?

Eva Karczag: The Trisha Brown dance I love perhaps the most, is Water Motor. While I was in the company, I watched Trisha perform Accumulation with Talking plus Water Motor countless times, and I’ve looked at the video of Water Motor many more times. For me, it contains everything I loved about watching Trisha dance and dancing her dances. If the one dance I were to take with me was one I performed, it would probably be Glacial Decoy. The whole piece, and especially the duet, is an ecstatic physical ride.

Q: How did Trisha’s dances evolve during your time with the company?

Eva Karczag: During my time with the company her pieces became physically more challenging and complex. Her performances shifted from spaces and small theaters to large theaters. She started using music that was specially composed—such as for Son of Gone Fishin’ and Set and Reset—and continued to work with artists who created sets specifically for each piece—Rauschenberg had created the set for Glacial Decoy and then for Set and Reset, Fujiko Nakaya for Opal Loop, and Donald Judd for Son of Gone Fishin’ .

Q: What stays with you the most about Trisha’s work today?

Eva Karczag: Her rigor, her passion, her commitment, her physicality, her intelligence, her humor, her desire to explore and openness to experiment, and her human-ness are some of the many things I absorbed while working with her. I hope these qualities are present in my work and interactions with others in all aspects of my life.

Photo by Nienke Terpsma.